Half a Century of The Bluest Eye: When White Insult Equates with Labour Pain

In the fall of 1941 no marigolds grew at the rise of World War II in the United States of America, it was kept quiet, analogously, Toni Morrison (1931-2019) wrote “The Bluest Eye”, her workshop-born debut novel, in refutation of American black beauty in the fall of 1970, it was kept quiet, from her colleagues of Random Publishing House, New York, as well. Pecola Breedlove entered into adult life and embraced motherhood prematurely at the age of 11 whereas Morrison stepped on the field of fictional world maturely at the age of 39.

In 1965, it was the time of turmoil when the whole country was in civil disobedience against racial intolerance and segregation, on the road to abolition of Jim Crow laws that separated the American nation between white and black in the name of equality, it was the time of tranquillity when Ms Morrison, a divorcée , a single parent and immensely in deep solitude, delved into black literature (both African and African-American writings on colonialism and slave narratives) and white literature (both American and European writings on imperialism and racial narratives) to find out the credible representation of black experiences in the United States, conversely, only she encountered with the white lies about the black justice, in addition, she got frustrated to know that merely all of them, except Mark Twain, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, either “escaped to notice” or “had chosen to ignore” to portray the black lives in American literature. Shockingly, the literature of black women writers in America was in vacuum; hence, she decided to write herself a book in which she could talk about “the aesthetics of blacks” and the epistemology of black women from a woman writer’s perspective that unlocked, probably, the literary discourses of women writings in the postmodern era prior to Elaine Showalter’s gynocritics (women as writers) and Héléne Cixous’ écriture féminine (women’s writings) in the seventies.

It was a secret until John Leonard, first reviewer of “The Bluest Eye” in The New York Times, wondered and wrote that “the novel becomes poetry” and titled it one of the three prominent novels on race in American literature back then. The book not only dealt with the sufferings and sadness of the black people imposed by the white people but also it broke the folds where black writers strived to glorify the black beauty, even so, it criticized the blacks for accepting the whiteness as their social status and dignity and for internalised self-loathing, humiliation and guilty because of their black identity. It also drew a real picture of black women’s socially constructed gender-roles that chained them in cages locked without keys, their complexes to prove their existence in the prison-like society, their agonies, anxieties and sorrows that were cloistered, secluded and unacknowledged and their dreams, hopes and desires to be loved. In a broader sense, the novel is about a journey of black women through the white gaze and white negligence in a segregated racial society and especially black guilty and black inferiority in a discriminated class system in the United States of America in the eyes of a black women writer in the time of the American civil rights movement in the sixties.

When Claudia MacTeer, the principle narrator in the different stages of her life, thought that they had dropped their seeds in their own little plot of black dirt just as Pecola’s father had dropped his seeds in his own plot of black dirt. Their innocence and faith had been no productive than his lust or desire, certainly, this fruition shed lights on the entire narrative and reflected Ms Morrison’s intellectual and moral rendition of racial tension and above all women experience at its best. The story centred on Pecola’s journey when she was at the verge of her childhood- the transition period- when she was regarded as ugly and unwanted by the community, classmates, and teachers and even by his friends, she wished to get blue eyes which she considered as a standard of beauty, social recognition and being lovable, she was ready to present herself at any form if it gave her the cherished eyes, as a result, when Cholly Breedlove with “the hatred mixed with tenderness” raped her and she could not resist and even she allowed him to do the incest second time and let herself throwing out her innocence, her girlhood and; let herself ruin and impregnate with her father’s baby; and let herself carry the unbearable weight of womanhood prematurely; and it was happened, in this case, only because she was black, she was ugly as the omnipresent third person narrator anatomised Pecola’s appearance of “the eyes, the small eyes set closely together under narrow forehead. The low, irregular hairlines, which seemed even more irregular in contrast to the straight, heavy eyebrows which nearly met. Keen but crooked nose, with nostrils. They had high cheekbones, and their ears turned forward. Sharply lips which insolent called attention not to themselves but to the rest of the face. You looked at them and wondered why they were so ugly; you looked closely and could not find the source. Then you realized that it came from conviction, their conviction.” As if the ugliness and deformation were her sin derived from the absolute entity that bounded her to self-loathing and to make herself desirable she wished to behold the blue eyes. On the other hand, as a well wisher, Claudia and Frieda sacrificed their “seeds, money and two dollars” but the nature and the all-powerful being discarded their prayer.

This book also depicted the discrimination, humiliation and abhorrence among the varied classes in the black community which sometimes outnumbered the racial revulsion which was a very unique trait against which Ms Morrison condemned the precedent writers, both black and white, for ignoring the violence and negligence among blacks thought they were the by-products of racism. When Pecola befriended with her classmate Maureen, a “high yellow dream child” with interracial complexity, had a high opinion herself as more respectable than colour of people, at last, humiliate Pecola for her skin; then appeared Louis Junior, son of Geraldine, a privileged black woman who regarded herself more “civilised” than other blacks and kept separateness like white did, allured her to his home for playing and vilely prison her with her mother’s beloved cat for which he was deprived from Geraldine’s affection and attention, as repressed and disturbed child he tortured Pecola and the cat but when Geraldine appeared in the house he throw the total guilt on Pecola’s shoulder. These two vignettes show us the class among the intersections in the black community is as productive as the race among the sections in the American nation to sprout tonnes of pains and sufferings.

Claudia MacTree , an archetype of counter-racism and a resistant against class complex, with her sister Frieda, stalked Rosemary Villanucci, their next-door neighbour who always teased them, in reaction Claudia wanted “to poke the arrogance out of her eyes and smash the pride of ownership that curls her chewing mouth” and assaulted her physically and they thought if she offered them “something precious” to get rid of, then they would show their “own pride must be asserted by refusing to accept”. Furthermore, Claudia denied enjoying drinking milk from Shirley Temple cup who failed to attract her as a standard of American beauty, in another scene, she ragged and ruined, with rage mixed with hatred, the blue-eyed dolls she got as a Christmas gift “but dismembering of dolls was not the true horror. The truly horrifying thing was transference of the same impulses to little white girls.” Whereas Pecola surrendered herself completely to self-loathing because of racial pressure, oppositely, Claudia took stand utterly with counter-negligence against all socially manufactured definitions of identity and standards that led us to all the discrimination, inequality and injustice.

The novel also uncovered the buried sighs, cries, yearnings, pains, agonies, sorrows and sufferings deep inside the black women’s heart mixed dried tears that were break open when Pauline Breedlove was crying out with tremendous pain to give birth Pecola in the hospital and roaming around with the stream of memories of white insult of previous white employer who in disgust forced her to divorce husband, Mr. Cholly Breedlove and thought, ‘Who say they don’t have no pain? Just ‘cause she don’t cry? ‘cause she can’t say it, they think it ain’t there? If they look in her eyes and see them eyeballs lolling back and see the sorrowful looks, they’d know.’ This monologue so heart-drenching to feel what was going through the black lives from the beginning unwritten in history books which Ms. Morrison equates the racial insult with the labour pain.

The knowledge of sex and the discovery of human body are two tools to explore the human pain and pleasure that centred on Pecola, Claudia and Fireda’s actions and conversations throughout the novel. Their surveillance on Mr. Henry lustrous and adulterous moments with Maginot Line and other prostitutes gave them a glimpse of human sexual life and when Mr. Henry mistreated Frieda and they analogized this molestation with Soaphead Church’s caress. When Pecola being raped by her father and miscarriage her unborn and being mad she was beating the air, Claudia assumed that only her father “loved her enough to touch her, envelop her, give her something of himself to her.” She believed in the sex as a medium of being loved and being freed from the guilty of ugliness.

Morrison repeatedly scattered her attention to the question of love in the narrative, what makes us the object of love – is it “Eat fish together,” “choking sounds and silence,” or “Love is never any better than lover. Wicked people love wickedly, violent people love violently, weak people love weakly, stupid people love stupidly, but the love of a free man is never safe. There is no gift for the beloved. The lover alone possesses his gift of love. The lover alone possesses his gift of love. The loved one is shorn, neutralized, frozen in the glare of the lover’s inward eye.”

After the Second World War when the whole world was passing through the existential crisis searching the meaning of life and individual’s identity and amidst the American civil rights movement when everyone was demanding their own dignity, equality and rights and the literary world entered into the postmodern era, Morrison emerged with her from breaking , and experimental novel with an allusion from “Dick and Jane” repeated three time in different forms with and without capitalizations, punctuations and space gap, non-linear plots and multiple point of views overlapping with each other . After she won the Nobel Prize in Literature as a first African woman for her “visionary force and poetic import” in 1993 she added an afterword at the end of the novel and wrote “the novel tried to hit the raw nerve of racial self-contempt, expose it, and then soothe it not with narcotics but with language that replicated the agency I discovered in my first experience of beauty.”

The story happened in Lorain, Ohio as it was also Morrison’s birthplace and the idea of the story of cherishing blue eyes was sourced from her childhood friend. Though Morrison stated repeatedly that her narratives are not factual or historical, surprisingly, her stories, most of them, are the representation of all times where people are suffering from racism. Her last paragraph of “The Bluest Eye” where she stated, “the land of the entire country was hostile to marigolds that year. This soil is bad for certain kinds of flowers. Certain seeds it will not nurture, certain fruit it will not bear, and when the land kills of its own volition, we acquiesce and say the victim had no right to live.”

_-_Hap_Hadley_poster.jpg)

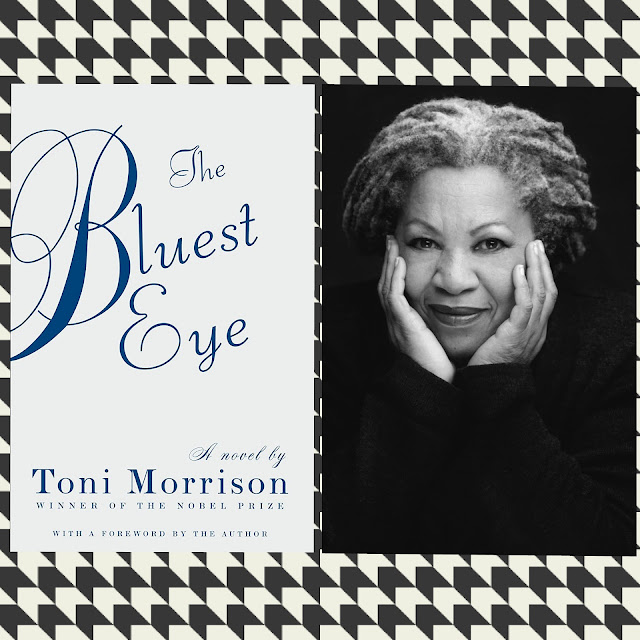

A monumental writer that shaped the world as it.

ReplyDelete